- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

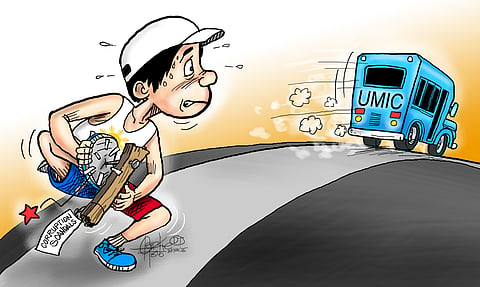

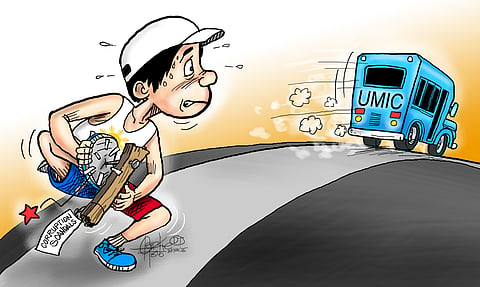

Unless the government shows a greater determination in prosecuting the crooks in government, the country may have to say goodbye to its aspiration to become an upper-middle-income country (UMIC).

The country missed the World Bank cutoff by just $26 last year as its Gross National Income (GNI) per capita reached $4,470 in 2024, just shy of the $4,496 threshold.

The corruption scandal involving the highest officials swept away the efforts to improve the investment climate that had gained traction, particularly after the enactment of Republic Act 12252, which amended the Investors’ Lease Act and extended the maximum lease period for private lands from 75 years to 99 years. The old law only allowed up to 50 years, renewable for an additional 25 years.

The new law is intended to attract long-term investors to counter the largely speculative portfolio capital, which is very volatile.

Foreign capitalists behind big-ticket ventures, from industrial estates to tourism estates and large-scale agribusiness, have long pushed for the enactment of a law that would serve as a de facto substitute for a constitutional amendment on land ownership, a political undertaking far more arduous and contentious.

Business leaders worry that the wait-and-see attitude among investors will persist until next year, as the pace of investigations and prosecutions of the corruption suspects remains disappointing.

The other day, the Independent Commission for Infrastructure and the Department of Public Works and Highways recommended plunder charges against two of the principal players.

Still, it was seen as a move to cover lost ground as the public outrage reached dangerous levels.

Even the holiday season, when consumer spending traditionally picks up to fuel a final spurt in the economy, is expected to be tepid due to low consumer confidence.

The uncertainty stems from the frequency of street demonstrations with increasing mobilization.

For instance, Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry Chairperson George Barcelon said the fluid situation will make households with members who have received their bonuses hold back on spending.

Instead of splurging with the extra money, many will consider setting aside the money for any eventuality.

The other aspect is the weak peso, which puts pressure on prices, particularly electricity and gas.

While remittances and exports benefit from the weak peso, the effect of an inflation spike offsets the gains.

Some Filipinos residing abroad are holding back on their dollar transfers, waiting for the peso to hit 60 to a greenback.

The two factors are now being watched, even as the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas is suspected of flooding the market with dollars to stem the depreciation to P60 per US dollar.

That form of anticipating the situation, if not addressed soon, affects remittances, which in turn limit relatives’ access to liquid funds to spend.

The political friction between the Duterte and Marcos forces remains a serious concern that may persist until 2028, when the next elections are scheduled.

An instability that will last long will be untenable as it may progressively weaken the economy.

What happens next may well decide whether the nation sinks or stays afloat, with skepticism running high over allegations of a sweeping cover-up.