- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

I studied literature in college, and part of my studies included analyzing the language used in the stories we tell. Not just the words, the rhythm and flow, or even the topics themselves, but the lens through which we view the world and how we shape truth in our narratives. This lens is not exclusive to creative writing; it shapes journalistic storytelling, political discourse, and social critique. Understanding it is vital, especially when language can empower, or dehumanize.

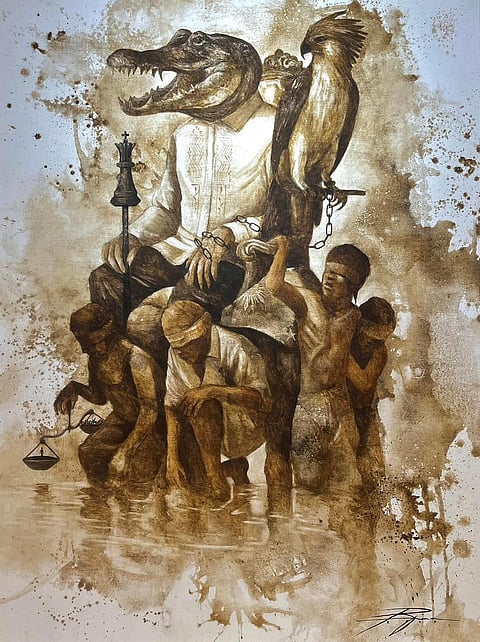

Currently, I am following the investigation into the flood control scandal. Writing about the probe and providing critical commentary as the case drags on, I find myself immersed in the fury that grips nearly every Filipino: anger at corruption, at greed and negligence that destroyed lives and homes. With that anger comes the instinct to use certain words for those implicated. I particularly am given to calling them “crocodiles” (“buwaya”).

Yet, I pause as I recall what I have learned.

The language we choose has consequences. Dehumanization is not new. History is rife with examples of language being weaponized to strip groups of their moral worth. The German Nazis called Jews Untermenschen ("subhuman") or "rats." Hutus during the Rwandan genocide called Tutsis "cockroaches." Colonial powers labeled indigenous populations as “savages.” Slavery, human trafficking, torture, and genocide all relied on dehumanizing language as a moral pretext. David Smith, author of Less Than Human, writes that dehumanization “subverts the natural inhibitions” humans have against harming others. Michelle Maiese, philosophy professor at Emmanuel College, defines dehumanization as “the psychological process of demonizing the enemy, making them seem less than human and hence not worthy of humane treatment.”

Dehumanization, then, is not only rhetoric. It sets the stage for moral injustice, allowing harm to be rationalized. If a group of people is less human than others, then it becomes easier for us to ignore human rights abuses, or worse yet, inflict actual, direct harm ourselves. Moreover, when people are framed as morally inferior or dangerous, the conflict becomes zero-sum: victory for one side justifies punishment or harm for the other.

In the Philippine context, dehumanization has traditionally been wielded by the powerful against the powerless. In the flood control scandal, particularly, political elites dismiss the hardships of ordinary citizens, flaunting wealth and privilege while framing critique as ungratefulness. One notorious nepo baby remarked, “Wala kaming utang ng loob sa mga Pilipino!” (“We owe nothing to the Filipino people!”), reflecting a moral inversion that privileges inherited wealth over social responsibility. Phrases like “Bakit di kayo mag trabaho?” (“Why don’t you work?”) reduce systemic poverty to individual failure.

In response, the masses have turned the tables, using language like “buwaya” to symbolize greed and predation. This is not dehumanization in the historical sense; it is a reflective, morally pointed critique.

Yet, here lies the challenge: how do we ensure that in condemning corruption, we do not adopt the very methods of dehumanization employed by those we oppose? After all, the ethical line we draw is subtle, yet crucial. Brené Brown notes that setting boundaries and maintaining emotional and physical safety are crucial for human empathy. In other words, while we may express anger and disdain, our criticism must be grounded in moral clarity, evidence, and reason. Not just emotional projection.

Psychological research also confirms the dangers of unmoderated dehumanization. Florence Enock and Harriet Over found that describing groups with animalistic terms increases willingness to endorse harm against them, even when they would otherwise be protected under moral norms. Nour Kteily of Northwestern University adds that groups who perceive themselves as dehumanized often dehumanize in return, creating a vicious cycle of escalating animosity.

As citizens, our moral responsibility is to engage critically. Criticism should focus on actions and evidence rather than the person as an absolute moral entity. Expressing outrage, as the public has done in the flood control scandal, is justified⸺but it becomes morally corrosive when it ignores facts or denies human complexity. Maintaining moral rigor does not diminish anger. Rather, it channels anger into accountability, advocacy, and systemic reform.

Dehumanization, whether in historical or contemporary contexts, is ultimately about power: who gets to define moral worth, and who gets to escape accountability. By recognizing this, Filipinos can wield language as a mirror to the powerful, highlighting their inhumanity without surrendering our own. Calling someone “buwaya” highlights systemic greed and inhumanity in their actions. It is not an endorsement of personal cruelty.

This is not to curtail the outrage of the people, or to order them on how they will express anger that is justified and necessary. On the contrary, it is to sharpen it, to channel it into effective, informed criticism. Sophia Smith Galer notes that words can hurt and influence behavior profoundly, shaping perceptions of who is deserving of empathy or harm. If our outrage is guided by evidence⸺if we focus on the corruption, the legal violations, the human cost⸺we uphold our own humanity while demanding meaningful accountability. Listening to affected communities, documenting evidence, and framing critique around actions rather than personal attacks strengthens both the call for justice and our moral stance. It also prevents factions and color-coded politics. By nuanced and logic-based criticism, the Filipinos can then choose their leaders by merit and not name or title alone.

Let us remember and reflect upon Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous quote: “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.”

At the end of the day, we are on the side of the masses. Our words must reflect that allegiance, channeling righteous anger into reasoned critique. We are not “buwaya” ourselves. We are human, demanding justice, integrity, and accountability from those who have forgotten that they are meant to serve.

Brené Brown, Dehumanizing Always Starts With Language, 2018.

Brené Brown, Words, Actions, Dehumanization, and Accountability, 2021.

David Livingstone Smith, Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others, 2011.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, 1886.

Michelle Maiese, Dehumanization, 2003.

Nour Kteily, Dehumanization: trends, insights, and challenges, 2022.

Sophia Smith Galer, The harm caused by dehumanising language, 2023.

Florence Enock & Harriet Over, Exploring the ‘Paradox of Dehumanization’: References to Human Specific Traits and Mental States are Frequent in Dehumanizing Propaganda, 2023.