- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

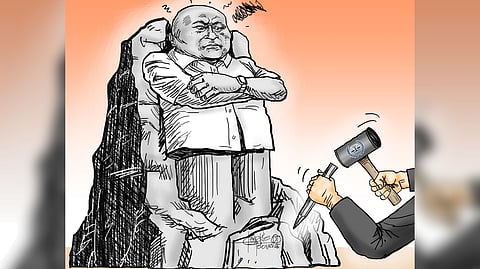

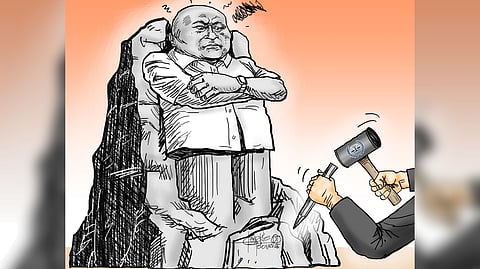

Legal experts said the only way an International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrant can be enforced against Senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa is through a surrender.

While the Supreme Court’s (SC) rules on extradition would not apply — requiring a domestic procedure before Dela Rosa is handed over — questions regarding sovereignty, which were raised during the surrender of former President Rodrigo Duterte to the ICC, have resurfaced.

Former SC Associate Justice Noel Tijam posed questions for the government to ponder regarding the intrusive nature of an ICC action against a Filipino citizen.

“If there is an ICC warrant of arrest and the same is enforced, is it legally enforceable?” he asked.

The Philippines ratified the Rome Statute in 2011 but took back its signature in 2018, with the withdrawal taking effect on 17 March 2019.

Post-withdrawal, the government is no longer obligated to cooperate with the ICC, including arresting and surrendering its nationals.

The government has insisted that Duterte’s 2025 arrest was conducted under an International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol) warrant and not the ICC’s. Still, critics argued it violated Philippine sovereignty because it did not go through a local court.

A legal precedent is provided under a 2021 SC ruling in Pangilinan v. Cayetano, which upheld the validity of the country’s withdrawal from the ICC without requiring Senate concurrence but indicated a residual cooperation in pre-withdrawal proceedings.

The High Court’s decision, however, qualified that the need for cooperation is non-binding in enforcing post-withdrawal warrants.

Another consideration is the absence of an implementing legislation that fully incorporates ICC warrants into local court procedures for automatic enforcement.

Republic Act 9851 (Crimes Against Humanity Law) requires surrenders to align with binding treaties, which the Rome Statute no longer is.

While an ICC “surrender” is not extradition, it still needs domestic enabling mechanisms, which are absent.

Another issue raised is the level of respect that the country is giving up with the political move.

“Will ASEAN neighbors respect us or disrespect us for surrendering our sovereignty and independence?” the ex-magistrate asked.

Relatedly, he queried, “Will it entice or discourage more foreign investments?”

An economist said surrendering another political opponent would escalate tensions between the Marcos administration and Duterte loyalists, thereby amplifying the risk of instability.

Political strife has been cited by analysts as a core barrier to foreign direct investments (FDI), rating the Philippines among the lowest in Southeast Asia for stability.

While the government and anti-Duterte critics argued that complying with the ICC orders builds confidence by bolstering rule-of-law credentials, independent sources believe that discouragement through amplified instability would result if enforcement sparks mass protests or legal battles in the runup to the 2028 presidential elections.

Economists indicated that recent moves towards liberalization, such as the 99-year land lease and reduced foreign ownership restrictions, continue to drive FDI growth, but political risks remain the “missing link.”

If the warrant is confirmed and enforced smoothly without major unrest, any discouragement would likely be short-lived, according to a political pundit.

At the very least, Dela Rosa’s arrest could prompt the Supreme Court to issue a landmark ruling on residual cooperation after the country’s withdrawal from a treaty.

Ultimately, the effect of another “surrender” would be a diminution of self-respect, particularly affecting the judiciary, which is notorious globally for being snail-paced.

Those in the administration should also be wary of the intent of those who side with international bodies in applying domestic justice.

These pro-ICC groups are destabilizers in disguise since, all things considered, they intend to prove the existence of weak institutions.