- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

[Caution: Article contains violence]

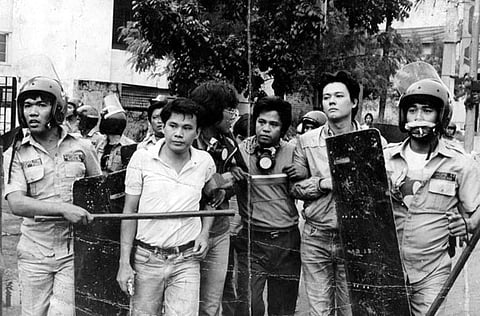

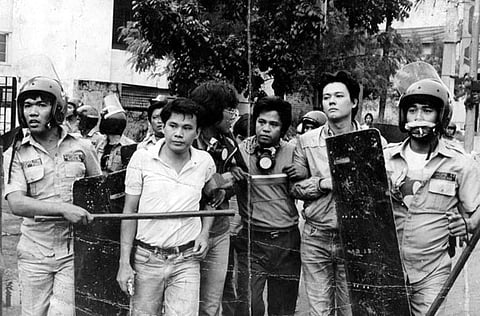

For those who lived through Martial Law, it remains one of the darkest times in the country’s history, a regime of terror and lasting trauma. A television and radio broadcast in September ignited the political landscape, sparking activism in the hearts of many.

Different names and different stories emerged from the same political milieu, yet all carried the weight of emotional, mental, physical, and historical trauma. The Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission documents these experiences, drawn from among the 70,000 people arrested, 34,000 tortured, and 3,240 victims of extrajudicial killings.

Laura and her husband, Justiniano, lived in Eastern Samar, a province where communist activity was widespread at the time. In April 1982, Capt. Quijano, a local Infantry Battalion leader, declared one of the key areas in Eastern Samar as a “no man’s land,” forcing residents, including the couple, to evacuate to a nearby barangay. There, officials arrested Justiniano without a warrant. When Laura tried to visit him at the military barracks, she was also taken.

At a nearby elementary school along the highway, Laura endured horrific abuse. While four soldiers pinned her arms and legs to the ground, she was raped. According to HRVVMC, Laura recounted how the soldiers “inserted [their] sex organ into [her] sex organ, one after another.”

The assault left Laura pregnant, straining her marriage. Justiniano could not accept either the unborn child or what had happened to her as excuse. Under pressure and without support, Laura aborted the three-month-old fetus. Her husband abandoned her, leaving her to bleed for several hours.

Another testimony from Samar comes from Javier, a man in his thirties. After fleeing his village with his family to seek safety, he was unjustly arrested while bringing his sick father to a municipal health center. At the military camp, he was tortured to confess being a member of the New People’s Army (NPA). Soldiers then humiliated him publicly by forcing him to walk carrying a car wheel around his neck from the camp to the checkpoint where he had been captured.

Javier was eventually freed only after a neighbor recognized him and confirmed that he had just recently moved into the barangay.

Tobias was apprehended by members of the Civilian Home Defense Forces (CHDF) while visiting relatives to inform them about his aunt’s passing. He was tortured and brought to a municipal jail in Zamboanga del Sur, where he was hogtied.

His uncle Fabian went to the jail and asked the chief of police to keep Tobias there until after the funeral. However, the next day Fabian was told that Tobias had been transferred to another division in Zamboanga del Sur, though no trace of him could be found. Three days later, a neighbor named Lino revealed that he had witnessed CHDF taking Tobias, still hogtied, to an old graveyard. Fabian and other relatives went there and discovered Tobias’s lifeless body in a tomb, bearing clear signs of torture.

In late 1973, on his way to his aunt’s house, he was intercepted by a Philippine Army task force and the Criminal Intelligence Service. They assaulted him, striking his lower back with a shotgun and punching him repeatedly. He was then brought to the local police station in Iloilo, where he was interrogated, stripped, and beaten multiple times with a .45 caliber pistol. Afterwards, he was detained at a military camp, where he endured one of the common torture methods of the era—Russian roulette.

Days later, he was again interrogated about a specific person and location. After over a year in detention, he was finally released on the condition that he report to the Provincial Commander every Saturday.

Gabriela, like her name that symbolizes the women’s movement in the country since the Spanish revolution, she was also a young activist at the time of Martial Law. Like many protestors, she sought justice for human rights abuses, which led the military to brand her a threat. With no food or shelter, she fled to the mountains with her infant child to seek safety.

In 1974, she surrendered under the assurance that she and her fellow activists would be granted amnesty and not imprisoned. That promise, however, was broken. Gabriela and her son were taken to a military camp in Sorsogon, where they endured harsh living conditions, plagued by insect and mosquito bites.

One night, Captain del Pilar, a commanding officer of the local Infantry Battalion, threatened her by pulling her hair with one hand while pointing a .45 caliber gun with the other. “Ano, lalaban ka? (Will you fight back?),” he yelled. “Pwede kitang patayin at sabihin ko na inaagaw mo ang baril ko kaya ka nabaril! (I can kill you and just say you grabbed my gun, that’s why you were shot!).” Fearing for her son’s life as he slept nearby, Gabriela submitted to him as he raped her. The assault was repeated later that same year.

Though eventually released, Gabriela was continually summoned by the military and pressured to cooperate against her former fellow activists. This caused others to believe she had defected. At times, she and other women her age were also forced to entertain high-ranking officials.

These are just some of the real stories from the past that continue to haunt us today. These accounts of violence serve as lessons that shaped the nation as it regained its democracy. 21 September is not merely the anniversary of Martial Law, but with the protests happening, the day is a reminder that such social injustices must never happen again, especially at the hands of our fellow Filipinos.