- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

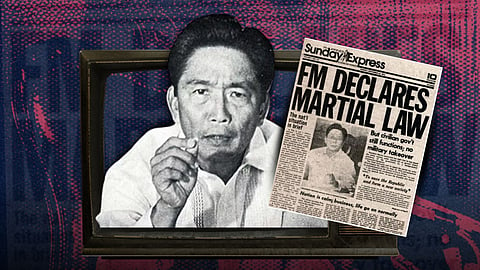

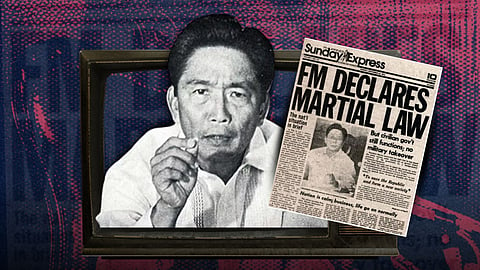

It was on 21 September 1972, that President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law through Proclamation No. 1081, citing threats from communist and Islamic insurgencies as justification. This proclamation allowed him to assume extensive powers, effectively sidelining the Constitution, judiciary, and press.

The political economy of the martial law regime became known as a “conjugal dictatorship” of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, characterized by “crony capitalism” and a “kleptocracy” of the first family and their favored oligarchs. Data from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s indicate significant decline in the standard of living, including decreased real wages, increased poverty, inflation, unemployment, and external debt. Massive deforestation reduced the country’s forest cover by nearly half. In regional terms, the Philippines lagged behind neighbors such as Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia, which were undergoing rapid industrialization.

According to University of the Philippines professor Alex Brillantes Jr. in his 1987 treatise Dictatorship & Martial Law: Philippine Authoritarianism in 1972, Marcos’s administration justified martial law in three ways: as a response to plots against his government, as a result of political decay after the failure of American-style democracy, and as a reflection of Filipino society’s supposed need for authoritarian leadership. The first two were explicitly stated in Proclamation No. 1081: “to save the republic” and “to reform society.”

Although Marcos claimed that he declared martial law in response to violent acts in 1971–72, such as the Plaza Miranda bombing and the alleged assassination attempt on Enrile, preparations were in place much earlier. Mijares wrote: “The beginning infrastructure for martial law was actually laid down as early as the first day of his assumption of the Philippine presidency on December 30, 1965.”

By 1972, Marcos had secured the loyalty of the Armed Forces, appointed eight of 11 Supreme Court justices, gained the backing of the Nixon administration, and crafted a favorable public relations environment to ensure initial acceptance of martial law.

Historians note that while preparations began as early as 1965, drafting of Proclamation 1081 itself started in December 1969, following Marcos’s expensive reelection campaign. He tasked cabinet factions to study how martial law should be structured.

To rewrite history, Marcos declared 21 September as “National Thanksgiving Day,” erasing the events of the Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties (MCCCL) rally and Senate hearings led by Senators Jose Diokno and Benigno Aquino Jr. The televised announcement took place on 23 September, creating public confusion.

Martial law was ratified by 90.77 percent of voters in the 1973 referendum, though its legitimacy was heavily questioned. A constitutional plebiscite soon followed, replacing the 1935 Constitution with a new one that shifted the Philippines from a presidential to a parliamentary government. Marcos remained in power as both head of state and head of government, consolidating control through the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) and the Batasang Pambansa.

Sources:

Mijares, Primitivo (2017). The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. Revised and Annotated Edition. Ateneo de Manila University Press.

De dios, E.S., Gochoco-Bautista, M.S., & Punongbayan, J.C. (2021). Martial law and the Philippine economy. Discussion Paper No. 2021-07. University of the Philippines School of Economics.

Brillantes, Alex B. Jr. (1987). Dictatorship & martial law: Philippine authoritarianism in 1972. Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Diliman School of Public Administration.

Magno, Alexander R., ed. (1998). "Democracy at the Crossroads". Kasaysayan, The Story of the Filipino People Volume 9:A Nation Reborn. Hong Kong: Asia Publishing Company Limited

Kasaysayan : the story of the Filipino people, Volume 9. (1998) Alex Magno, ed. Pleasantville, New York: Asia Publishing Company Limited.

Almonte, Jose T. and Vitug, Marites Dañguilan. (2015) Endless Journey: A Memoir. Quezon City: Cleverheads Publishing, 77.

Celoza, Albert F. (1997). Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism.