- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

This was a written review from Graham’s Lady Magazine, upon the release of this scorching yet abominably thrilling story written by someone called Ellis Bell — later on to be revealed as the pen name of who would eventually become one of the most memorable and renowned authors in literature and one out of the three famous literary sisters in history.

Wuthering Heights was Emily Brontë’s only novel to ever be published, as she died from consumption in 1848, not even too long after the publication of the novel, which came about along with her sisters’ own works: Jane Eyre by Charlotte and Agnes Grey by Anne.

Critics at that time recognized the power and intense imagination of the novel, but were taken aback by the storyline, and objected to the savagery and the ruthlessness of the characters. And yet, to this day, even after hundreds of years have passed, the novel has been thoroughly studied, referenced in pop culture, sung or written about in unforgettable songs, and like almost every book that stands as a classic, has been adapted into TV or film.

In the 1939 film adaptation, Heathcliff is played by Laurence Olivier (to which his performance earned him an Oscar nomination), opposite Merle Oberon’s Cathy. Although the film was well received, Olivier’s Heathcliff is more stern than impassioned and ruthless. The 1939 version lacks the zeal and, yes, morbidity necessary to convey the intensity and anguish of Catherine and Heathcliff’s relationship. The entire film works to warp Brontë’s vision into this bittersweet tragic love story on the surface. But Wuthering Heights is one that nowhere falls under a sugary Hallmark movie-typebeat category.

Not every film attempts to sanitize the novel’s brutality, yet even the most faithful of adaptations are flawed.

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, released in 1992, works to evoke the novel’s eerie and gothic mood and reconstructs much of the plot. Ralph Fiennes is a delightfully disturbed but thoroughly human Heathcliff, with a conflicting and frustrated Cathy portrayed by Juliette Binoche, their performances and their chemistry being one of the strongest aspects of this film (they would later go on to work in The English Patient). The film shows us the character’s subjection to years of physical and verbal abuse, particularly at the hands of an aptly detestable Hindley Earnshaw. The film also captures the intensity of Heathcliff’s and Catherine’s childhood bond. But the film ignores what the novel makes clear: the primary motivation behind Heathcliff’s mistreatment is racism. Cathy’s decision to dissolve their childhood bond and marry the more suitable, well-born Edgar Linton is informed by classist and racist norms.

Other loose adaptations come into mind, such as the 1954 adaptation, retitled Abismos de pasión, directed by Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel and set in Catholic Mexico, with Heathcliff and Cathy renamed Alejandro and Catalina and Hihintayin Kita sa Langit (1991), with a modern setting taking place in the northern province of the Philippines. There is also a 1985 French film adaptation, Hurlevent by Jacques Rivette, and a 1988 Japanese film adaptation by Yoshishige Yoshida.

Nevertheless, Wuthering Heights still holds a reputation as being “hard to film,” which is why some versions have cut the story back. Rather than attempt to follow the two generations of the book, they concentrate only on Cathy and Heathcliff, making them the sole focus of the story and ending an adaptation once it reaches Cathy’s demise and the spiral Heathcliff leads himself into shortly afterwards, but never the events taking place years later where we meet Catherine Linton and Hareton. And not only is the novel oftentimes difficult to translate onscreen because it depicts human beings at their most primal, but also because it is incredibly told in a strange way.

We learn their tale through an uninitiated southerner, Lockwood, who himself hears much of the story from Nelly, the servant. Crucial scenes in the book have an emotional realism drawn not only from the gloomy Yorkshire skies but also from gothic melodrama: Cathy’s ghost literally bleeds as it grasps Lockwood through a window; and very later on Heathcliff digs up Catherine’s grave just “to have her in my arms again.” And if this is realism, it is so extreme that it borders on the theatrical.

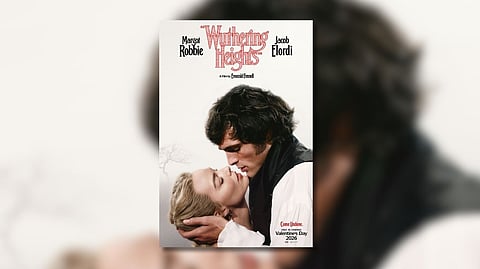

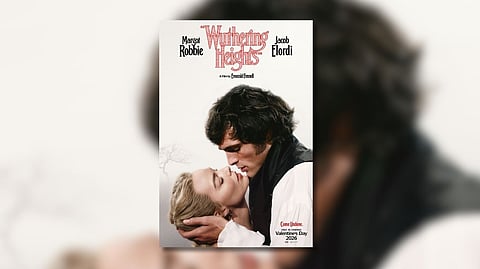

All this resurging talk regarding the novel and its previous onscreen depictions ties in with the upcoming movie adaptation, directed and written by Emerald Fennell which will be released in early 2026. It had been stirring controversy from the very first day its casting was announced online months before its release, as an amount of fans of the book have lamented Jacob Elordi’s casting as Heathcliff who is far off from the description of the character in the novel, and Margot Robbie portraying Cathy while being much older than the character herself, alongside the early marketing some have criticized as overly egregious.

Its recently dropped trailer immediately sparked plenty of critical comments on social media from avid readers and enjoyers of the Brontë’ sisters’s works. And once again, fans have argued that this adaptation seems more focused on aesthetic gloss and star power than capturing the raw, tumultuous core of Brontë’s original narrative. Much of the backlash revolves around the fear that Wuthering Heights will be diluted into yet another romantic period drama that overlooks the deeply disturbing psychological and social critiques embedded in the novel, as a reminder that Wuthering Heights has never simply been just about love. It is a tale about obsession, vengeance, classism, generational trauma and the haunting specter of unhealed wounds — such themes that are often lost or diminished in mainstream reinterpretations that try to make the story more palatable.

This leads to an ongoing question that haunts every retelling of Wuthering Heights: can it ever truly be adapted faithfully? The novel’s power lies in its structural complexity, its use of multiple unreliable narrators and its refusal to moralize or redeem its characters.

Heathcliff is not meant to be wholly romanticized, and Cathy wasn’t always shown to be likable. They are destructive, magnetic forces caught in a cosmic cycle of longing and loathing. While Emerald Fennell is known for her provocative and polarizing work, as seen in Promising Young Woman and Saltburn — it is unclear whether her upcoming adaptation will confront the full depth of Brontë’s vision or, instead, continue the trend of stylized misinterpretation. Fans are hoping for a version that embraces the chaos, the cruelty and the catharsis — and not one that sanitizes or simplifies.

What we can gather, however, from this long history of adaptations, successful or not, is that Wuthering Heights resists easy translation because it is not a conventional story. It is an emotional tempest; a narrative that rages like the moors on which it is set. Every attempt to adapt it, no matter how flawed, becomes another mirror reflecting how modern sensibilities wrestle with its brutal truths.

Perhaps that is the lasting legacy of Emily Brontë’s singular work: not that it is impossible to adapt, but that each adaptation serves as a haunting reminder of how wild and untamed the original remains: which is a literary ghost that refuses to rest.