- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

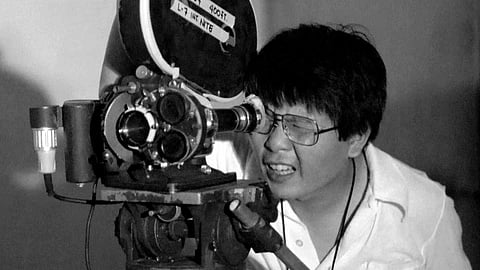

Mike de Leon (Miguel Pamintuan de Leon), one of the most brilliant and uncompromising voices in Philippine cinema, passed away on 28 August 2025. He was 78.

Born on 24 May 1947 in Manila, de Leon came from a family deeply rooted in the country’s film tradition. His father, Manuel de Leon, was a producer at LVN Pictures, while his grandmother, Narcisa “Doña Sisang” Buencamino vda. de Leon, was the legendary matriarch of the studio. After studying humanities at Ateneo de Manila University and art history at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, de Leon carved out his own place in film history — not by following convention, but by reshaping it.

Before his major works, de Leon made two short films, Sa Bisperas (1972) and Monologo (1975). That same year, he founded Cinema Artists Philippines, which produced Lino Brocka’s Maynila: Sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag, for which de Leon served as cinematographer. The film earned him his first Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences (FAMAS) award for cinematography and set the stage for his lifelong pursuit of cinematic truth.

His debut feature, Itim (1976), revealed a filmmaker of rare precision and sensitivity. It went on to win multiple Gawad Urian awards and earned him Best Director at the 1978 Asian Film Festival in Sydney, with Charo Santos taking Best Actress. He followed this with Kung Mangarap Ka’t Magising (1977), a tender meditation on love dedicated to Doña Sisang.

From the late 1970s through the 1980s, de Leon created some of the most searing works of Philippine cinema. Kakabakaba Ka Ba? (1980) blended musical comedy with political satire, while Kisapmata (1981) and Batch ’81 (1982) offered chilling portrayals of authoritarianism within the family and in institutions. Sister Stella L. (1984), starring Vilma Santos, became a landmark film for its bold depiction of labor struggles and social injustice during the Marcos regime.

These works not only garnered critical acclaim — earning Gawad Urian, FAMAS, and Film Academy of the Philippines honors — but also international recognition. Kisapmata and Batch ’81 screened at the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight in 1982, while Sister Stella L. was shown at the Venice Film Festival in 1985. Together, they established de Leon as a fearless chronicler of Filipino society.

Though disillusioned at times with the film industry, de Leon returned to filmmaking in 1993 with Aliwan Paradise, part of the Japan Foundation’s omnibus Southern Winds. In 1999, he released Bayaning Third World, a daring, self-reflexive investigation into the life and myth of José Rizal. The film swept the Gawad Urian, winning Best Picture and Best Director, and further cemented his reputation as an uncompromising auteur.

After nearly two decades of absence, de Leon came back with Citizen Jake (2018), co-written with Atom Araullo and Noel Pascual. While polarizing, the film reaffirmed his enduring commitment to cinema as a tool for truth-telling.

De Leon was not only a filmmaker but also a devoted guardian of Philippine cinema’s legacy. He spearheaded the restoration of Maynila: Sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag with Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation and the Film Development Council of the Philippines, an effort that won international preservation honors. He later worked on the restorations of A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino (1965) and Kisapmata, the latter screened at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna in 2020 and at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which dedicated a retrospective to his works in 2022.

Across his career, de Leon received countless accolades. Itim, Kisapmata, Batch ’81, and Sister Stella L. were all named among the Ten Best Films of their respective decades by the Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino. In 1999, he was honored with the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Centennial Honors for the Arts.

But more than trophies, de Leon’s legacy lies in his uncompromising vision. He resisted commercial pressures, questioned authority, and refused to turn away from difficult truths. His films, by turns intimate and confrontational, continue to resonate for their artistry and their unflinching engagement with Filipino life.

Mike de Leon leaves behind a body of work that is as challenging as it is essential, as aesthetically daring as it is politically urgent. In his images — haunting, beautiful, unsettling — we find not only the story of one filmmaker, but the story of a nation.

As the lights dim on his extraordinary life, his films endure: sharp reminders that cinema, at its best, is not just entertainment, but conscience, memory and art.