- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

Even the powerful Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noticed the flagging revenue collections in the Philippines as hampering its capacity to achieve its full economic potential.

In OECD’s report called Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2025, the Philippines’ tax-to-GDP ratio was 17.8 percent in 2023, among the weakest in the region and below the Asia-Pacific average of 19.5 percent.

Developed nations, comprising the OECD, have an average tax-to-GDP ratio of 33.9 percent.

The tax-to-GDP ratio measures the total tax revenue as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP) which reflects the country’s ability to finance public services, infrastructure, and social programs through taxation.

The lower the ratio, the more limited the fiscal capacity, which means a dependence on borrowings or foreign aid to raise funds for the yearly budget.

In the Philippines, the practice is to reallocate funds from yearly appropriations to areas that need augmentation. Unfortunately, these funds are often channeled to unproductive projects inserted by legislators in the annual budget.

These projects are primarily intended for kickbacks and patronage as they are not part of the administration’s development program or economic roadmap.

In the past three years, unprogrammed appropriations (UA) grew, which budget watchdogs said was the result of more items classified as pork barrel projects — such as flood control structures and multipurpose halls — being inserted into the budget.

The workaround for the 2024 budget was to set aside regular and sometimes crucial projects of agencies, particularly the Department of Public Works and Highways and the Department of Transportation, to be moved to the UA section of the General Appropriations bill.

The budget law of that year included a provision authorizing the Department of Finance (DoF) to sweep up excess funds from government-owned and controlled corporations to ensure that the UA was funded.

Thus, the DoF sought to reallocate P89.9 billion from the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. and P117 billion from the Philippine Deposit Insurance Corp. to cover some P200 billion worth of spending under the UA.

The UA creates fiscal space for discretionary spending, including pork barrel projects, as it avoids immediate borrowing or tax hikes; however, it strains GOCCs by reducing their financial buffers and risks prioritizing political projects over national priorities.

The flexibility enables congressional insertions and at the same time, dodges a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that declared the Priority Development Assistance Fund and any form of legislative pork barrel unconstitutional.

In the 2025 budget, most of the legislative pork was merely inserted in the bicameral conference committee, resulting in blank items that were later filled in before the enrolled bill was submitted to President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

Heavily directing the UA to pork barrel projects may not address structural revenue shortfalls, perpetuating a dependence on temporary measures rather than systemic tax reforms to boost the 17.8-percent tax-to-GDP ratio.

The UA has been growing because, unlike programmed appropriations which undergo detailed scrutiny, items under the UA can be released with less public oversight, increasing the risk of favoritism and corruption.

The Governance Commission for GOCCs (GCG) ensures compliance with remittance rules; however, funds of state firms are lodged in the UA, and these escape similar scrutiny as they become lump sums.

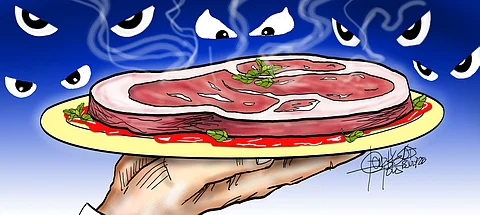

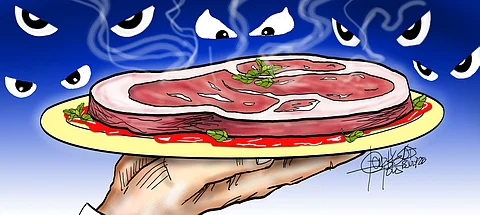

Trust the rapacious members of Congress to think of another way to raise the pork they crave in the 2026 budget.