- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

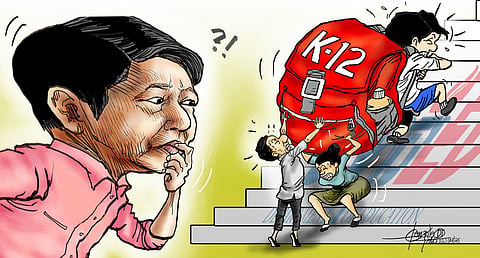

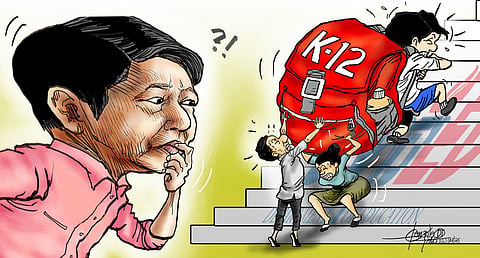

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s growing frustration over the K-12 program reflects a sentiment shared by many Filipino parents, educators, and even students: that after more than a decade since its implementation, the program has yet to fulfill its promise of producing employable high school graduates or improving the overall quality of Philippine education.

His criticism — that the K-12 system only adds financial burden without clear economic return — is not without merit. The questions he raised go to the heart of what education should be: a tool for empowerment, not a treadmill of hardship.

Introduced in 2012, the K-12 program added two years of senior high school to the basic education curriculum, with the stated goal of preparing students for employment, entrepreneurship, skills development, or further studies.

In theory, this was a reform designed to align the Philippine education system with global standards. In practice, however, it has produced more confusion and inequality than opportunities.

President Marcos’ view echoes the frustration of countless families struggling to finance those extra two years, especially in public schools where facilities remain inadequate and the curriculum often fails to meet industry standards.

In many cases, graduates of the senior high school program find themselves unemployable, as employers continue to prefer college graduates for even entry-level positions. The promise of job readiness after Grade 12 has, for the most part, fallen flat.

Worse, the Department of Education (DepEd) has been unable to fully equip public schools with the resources to properly implement the program. Teachers remain overburdened, some senior high school tracks lack qualified instructors, and learning materials are outdated or insufficient.

This has been compounded by the country’s broader learning crisis, which the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has flagged. Filipino students ranked among the lowest in international assessments in reading, math, and science — areas that are supposed to be strengthened by a longer schooling period.

In this context, President Marcos’s frustration is not only understandable — it is warranted. His remarks should not be taken as an outright dismissal of educational reform but rather a signal that the current iteration of K-12 is in dire need of rethinking. It’s a call for accountability and results.

Fortunately, new Education Secretary Sonny Angara appears to have taken this call seriously. He has announced a roadmap to overhaul the curriculum and address the learning crisis within a realistic timeline. His background as a legislator who has worked on education reform could be key in driving changes that are both systemic and targeted.

But reform must go beyond fixing the curriculum — it must also focus on teacher training, investment in school infrastructure, and closer industry-academe linkages to ensure job relevance.

What the K-12 issue reveals is a broader problem: educational reforms in the Philippines often suffer from poor execution, lack of political will, and disconnect from socioeconomic realities.

President Marcos Jr.’s open criticism may be just the nudge needed to push for a second wave of reforms — ones grounded not just in theory but in lived experience.

Ultimately, the goal of K-12 was noble, but nobility is not enough. If the program fails to deliver on its promises, then it is right for the government to reassess, recalibrate, and if necessary, redesign it altogether.

The frustration is not just justified — it is a necessary spark for long-overdue change.