- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

The 46th ASEAN Summit held 26-27 May in Kuala Lumpur was a landmark moment for the Southeast Asian regional bloc, China and the Gulf Cooperation Council comprising the Kingdoms of Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, the Sultanate of Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Qatar. Altogether, these entities boast a population of over 2.1 billion and a combined GDP of nearly $25 trillion.

However, a quick look at the results of the two-day gathering had analysts wondering about the summit’s substance. “More symbolic rather than substantive, at first glance,” said the chief analyst of a Singapore-based think tank who went on to say that “aligning three very different blocs is difficult and I really don’t know if this format can survive next year under the Philippines” chairmanship of ASEAN.

Still, there is no question about the eagerness of the participants to make the occasion more than just your standard summitry. The meetings were long, with some 14 bilateral and informal side meetings held between the leaders of the ASEAN member-states, their counterparts from the GCC and China’s representatives to the summit.

Observers said attempts at realignment resulting from the uncertainties caused by US President Donald Trump’s tariffs were quite apparent. The moves were designed by this year’s ASEAN summit host, Malaysian PM Anwar Ibrahim, to realize his vision of Malaysia joining BRICS.

BRICS is an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, and China, countries representing a group of emerging economies whose leaders initially met in 2009 to coordinate economic and diplomatic policies, and to explore the establishment of new financial institutions and lessen reliance on the US dollar.

The group was later expanded to include South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the UAE (BRICS+).

Anwar has been wanting Malaysia’s inclusion in BRICS as part of a realignment plan envisioned for Asia’s developing economies, particularly after Indonesia joined the bloc in 2024, the first Southeast Asian country to do so. Thailand and Vietnam, as well, share Malaysia’s interest in joining BRICS.

The underlying motive is basically the desire for economies within ASEAN to hedge against an unstable global environment, particularly with regard to uncertainties posed by the US’ current trade policy.

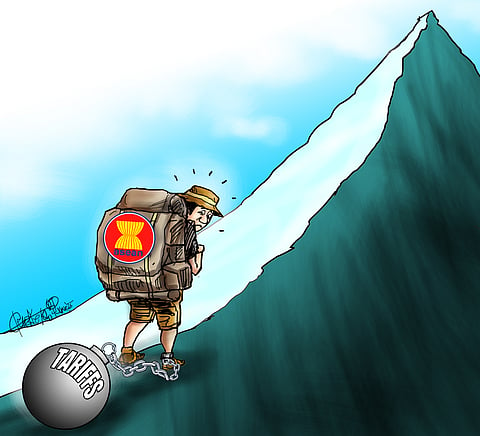

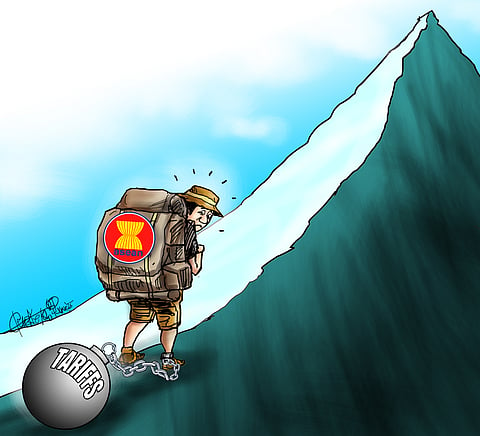

President Trump’s imposition of sweeping tariffs is rattling ASEAN supply chains, and the regional bloc is struggling to craft a united response beyond a non-retaliatory stand against the US.

Observed leading Malaysian academic Azmi Hassan, “ASEAN cannot speak with one voice when tariff exposure is so uneven,” illustrating, for instance, the 10 percent facing Singapore and 46 percent threatening Vietnam.

“Each of the individual ASEAN countries is negotiating bilaterally with the US, while ASEAN as a bloc is adopting a wait-and-see approach,” he said. “This is not just about buying time. This trilateral platform with ASEAN-China-GCC is actually meant to show pressure by diversification, rather than an outright pivot to China.”

Be that as it may, there is no denying that China looms large over ASEAN, and larger still, with the regional bloc poised for a painful battering when and if Trump’s tariffs begin to take effect.

But analysts point out that while, yes, China’s trade footprint in the region might be deepening, the US still dominates in terms of foreign direct investments, intellectual property and capital.

“We should not be seeing a replacement (by China of the US),” underscored Hassan, “just growing interdependence.”

Even as ASEAN, because of global trade threats, is compelled to lean towards more integration with China on trade, US-linked capital and innovation remain critical to the region’s economies.

At this point in time, ASEAN is left with little choice but to manage both sides, and the trilateral format such as that which was employed by the regional bloc at the summit in KL should not be seen as an ASEAN turning away from its traditional partners like the US or the EU.

Diversification has always been a positive part of ASEAN’s engagement strategy — a broad hedging strategy if you will — and the regional bloc must find a way to maintain its resilience and deepen its South-South (partnerships between developing countries) while keeping its ties with the West.

ASEAN’s diversified hedging strategy had served it well in the past, but the next decade will be its toughest test yet.

If ASEAN can deepen South-South ties without alienating the West — while maintaining internal unity — the regional bloc could remain a key player in shaping Asia’s future. If not, it risks becoming a mere battleground for great-power competition.