- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

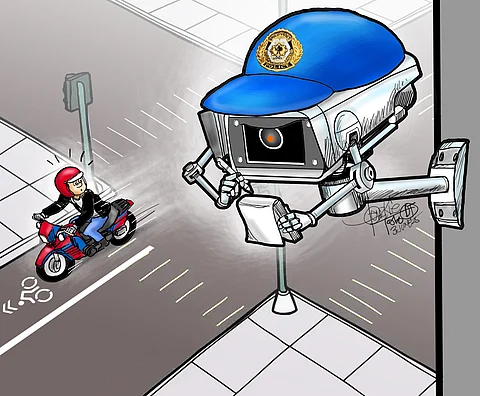

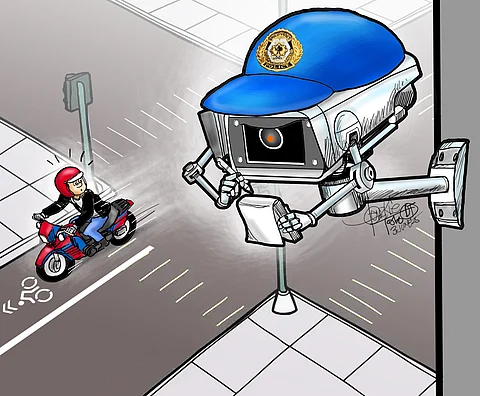

It’s almost comical, the way we argue over traffic enforcement in this country — especially now that the No Contact Apprehension Policy (NCAP) is back, sort of, after the Supreme Court (SC) partially lifted its temporary restraining order (TRO) on the scheme.

That action by the SC has allowed the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) to resume NCAP’s implementation on some of the choked arteries of Metro Manila. But as in many things in this republic, nothing is ever quite what it seems.

Juman Paa, the lawyer who filed the original petition, now wants the TRO reinstated. His argument? The MMDA justified NCAP’s revival based on the supposed urgency of EDSA’s rehabilitation — which, it turns out, has been postponed.

Malacañang says repairs will start after a month-long stay, but the MMDA has already raced to reimplement NCAP just days after the Court’s partial lifting of the TRO. Was it really about unsnarling traffic, or about revenues?

Let’s play devil’s advocate. The Philippines is not pioneering anything radical with NCAP. The world has long embraced automated enforcement.

London has speed cameras and congestion charging. Singapore — often held up as the paragon of urban planning — uses Electronic Road Pricing and a vast camera network to ensure traffic discipline.

Even New York, where jaywalking is practically a sport, employs school-zone cameras that helped reduce pedestrian fatalities by over 60 percent.

The argument is elegant: humans err. We are corruptible, fallible and selective. Cameras, on the other hand, don’t accept bribes. They don’t sleep. They don’t play favorites.

If we want order on our lawless roads, a camera seems the great equalizer. But herein lies the problem: that logic only works when the system behind the camera is just as reliable.

In Metro Manila, road markings are faded, traffic signs are obscured, and enforcement protocols vary from one street corner to the next. So is it surprising that NCAP once churned out thousands of erroneous violations?

And then there’s the matter of who gets penalized. NCAP here follows “registered owner liability” — meaning the person who owns the vehicle is presumed guilty until they can prove otherwise.

In most mature systems, there’s a clear path to transfer liability to the actual driver. Here, it’s more of a maze, with the burden falling squarely on the hapless car owner. It feels less like justice and more like bureaucratic shortcutting.

Public consultations? Transport sector coordination? Minimal. The revival of NCAP was abrupt and top-down — announced before the smoke even cleared on whether the conditions justifying it still held.

Other countries succeeded with automated enforcement because they built public trust first. They had the infrastructure. They had functioning dispute mechanisms. They had a government people could halfway believe in.

Do we? When motorists can’t trust a street sign, when even a clean license plate can lead to a phantom violation, and when state agencies rush to fine but crawl to correct — the answer is obvious.

NCAP is not inherently evil. In a better-governed country, it could be a blessing. Here, it feels more like surveillance without accountability — discipline imposed without due process.

The Supreme Court may rule on legality, but only the Executive branch can make it work. And that starts not with cameras, but with fixing the basics: clear roads, consistent rules, transparent enforcement, and a public that isn’t treated like a cash cow.

We are not putting the cart before the horse. We are putting the camera before the law.