- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

It is during the periods when the world’s attention is centered on it such as the ongoing Summit in Vientiane, Laos that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations exposes its failures or, to borrow the term of one regional expert, the bloc’s paralysis.

ASEAN is undergoing an identity crisis in its search of global recognition that approximates that of the European Union, yet its 10 nation members can’t agree if it is indeed an Economic Community.

Officially, the ASEAN Economic Community started in 2020 with its population of 650 million and, based on Asian Development Bank figures, a combined growth rate that makes it the global engine of development, outstripping the level of progress in other parts of the world.

Its vibrant and increasingly tech savvy young population makes multinationals consider it as the future global economic center, where innovation abounds while inclusivity is present, meaning that nearly the entire population in the region is prosperous which is lost to other corners of the earth.

ASEAN’s demographic power stands as a formidable driver of growth since an economy depends on the people who contribute to the gross domestic product.

The union of 10 nations, however, refuses to take up the cudgels for its members as the members of the group will always choose harmony, even if unprincipled, over disputes.

It underlines the principle of Unity in Diversity and the consensus process in which a disagreement by one means an issue is set aside.

Most of its members prefer the character of a neutral zone rather than being involved as a player in a strife-torn world.

The geopolitical reality militates against such a role for ASEAN, primarily due to the inclination of major powers to accumulate allies to back their positions.

It must insist on its inherent strength as a community to defend its members from aggressors and stand up for its economic interests as a bloc.

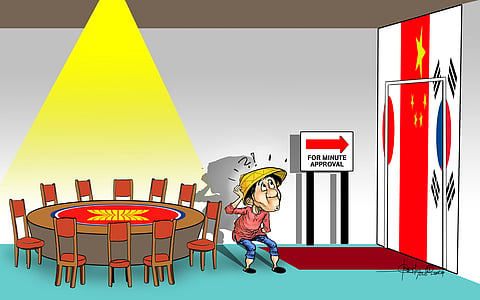

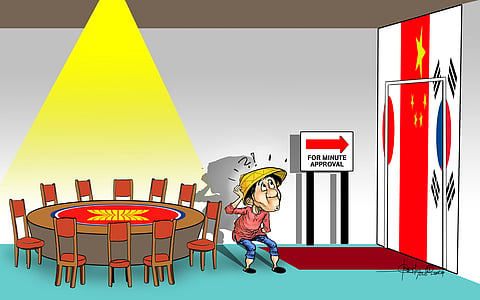

The current Summit indicates another instance of paralysis against China in which the Philippines had a hard time finding support for its position to make the Asian superpower recognize its irresponsible actions in the West Philippine Sea.

Asean’s vulnerability is reflected in its annual event where instead of the 10 nations plotting its course, the bloc needs to consult with its so-called +3 partners in the region, China, Japan and South Korea.

Soon it may become +4 or +5 depending on the demands of other nations such as Australia and New Zealand to be part of the decision-makers.

Instead of the positions taken as a community, the bloc accommodates several considerations from the partners, thus ending up with no action at all.

China can pursue its expansive sovereignty claims since it brushes aside Asean as having a clear position that makes it convenient for the superpower to deal individually with its weaker neighbors using aggression.

On paper, Beijing bases its claims on its own narrative of historical territorial rights, whereas Asean and the United States uphold existing international laws and norms that define maritime boundaries.

Despite Asean’s official support of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) which codifies maritime laws and norms, only the individual member states, specifically the Philippines, spoke out.

Due to the inability of the bloc to forge a solid position, China confidently classifies the Philippines as an “outlier” regarding their maritime conflict.

Malaysia at least made a stand, taking the course of keeping the peace through the status quo without resolving the issues, the same way that it has dealt with the Philippines regarding the Sabah question.

Even Vietnam and Singapore, which the Philippines has relied on as partners in making China respond to the call to respect international conventions, were noticeably silent regarding the conflict during the Summit.

Asean must have a clear stand as a bloc on issues affecting many of its members or it will continually fade into irrelevance.