- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

Anda, Bohol

Bohol’s tourism boom is founded on its prized attractions -- 1,268 mounds of limestone completely covered in brown earth, resembling hills of cocoa; minute lovable primates known as tarsiers, which would be downright petrifying if they were the size of a man; a two-kilometer stretch of mahogany trees that provides an escape from the cacophony of the city; a pleasant cruise on a lazy river; and spectacular beaches that showcase the coastal paradise. It is green all around, thanks to rice paddies, palm trees and coconut trees. The coastal road that loops around the island is clean and well-paved, a testament to effective infrastructure spending. But I am not in Bohol for those reasons. I came to appreciate art in a sort of visita iglesia.

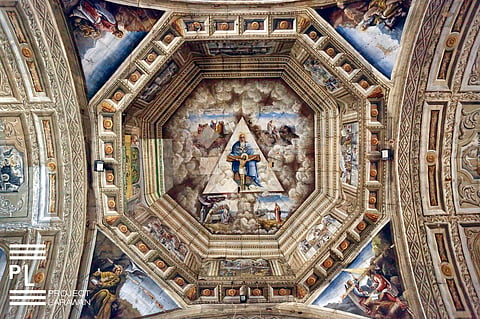

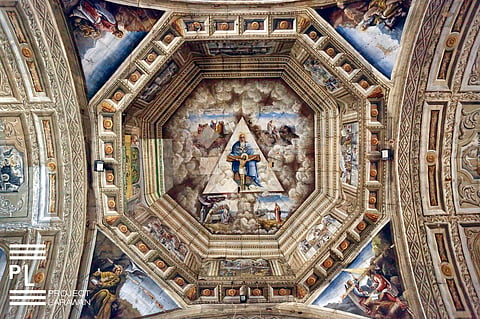

I am swooning over a jaw-dropping vista under a glorious dome sky, replete with symbolism and symmetry -- a feast of color and form erupting in brilliance. A magnum opus, lush with masterful brushstrokes, graces the ceiling of Anda Church. The Holy Trinity is the centerpiece: the bearded, white-haired Father, the crucified Son and the dove-represented Godly Spirit, aptly framed within the uniform sides of a triangle, advocating identical significance among the three divine entities.

Four quadrants emerge from a clouded realm, each flaunting a scene from Christ’s humanity or angelic encounters with church doctors or biblical characters. This stunning pageantry exists within an octagon, a combination of the perfect circle and the practical square, signifying a fusion of divinity and humanity; thus, one of Catholicism’s fundamental doctrines is expressed in this painted masterpiece.

The commanding sight is more than just art dazzling with visual impressions. The paintings are positioned in a revered setting -- on the ceiling of the church, a proxy for the heavens, stirring emotions and evoking a response.

Wow is the solitary word that escapes my lips. Otherwise, I am stunned into awed silence as I lay on the cold floor directly under the cupola, looking up in a state of rapture, conjuring visualizations of heaven. Sprawled on the ground is the best way to observe the ceiling at length without straining my neck.

Boo! A child’s face appears in my line of sight, looking down at me with an impish beam, momentarily blocking my view and breaking the spell. I contort my face into a caricature, and the boy hoots. Other kids join him and hover around me, only to run away shrieking when I scare them off with more ghoulish impressions, disturbing the local women seated on the pews, who are listening intently to a parish worker expounding on the church’s position on reproductive health. Initially mindful of the grown man spread out on the church floor like a drunk, they deem it harmless enough and shoo the children away, instructing them to leave me to my pursuit in peace. The youngsters depart reluctantly.

My attention returns to the ceiling. Art is not confined just to the dome, though it occupies the most important place in the cruciform layout. The entire ceiling is a broad, inclusive canvas; the altar, the nave and all sides of the vault are adorned with lofty vistas. The images are by Raymundo Francia, a painter commissioned by the archdiocese of the neighboring province of Cebu back in the 1920s to render the overhead interior surfaces of churches in Bohol with biblical scenes, Catholic doctrines and church narratives. Art was employed by the church to evangelize, convey meanings and educate the flock. What more effective means is there to communicate to a simple audience than through imagery? It made perfect sense to me.

Francia’s frescoes and masterpieces adorn the ceilings of Anda, Jagna, Balilihan, Loboc, Dauis, Loay and the other towns and municipalities of Bohol, his exhaustive collection entailing a significant portion of his life to complete. With his loaded paintbrush, Francia narrated the story of Christ’s passion and brought glorious scenes to the fore. He depicted captivating prophets, interpreted faith and religion, implied meanings and imparted insights, utilizing recurring themes and motifs, simplistic symbols and imagery. He braved the dizzying heights to unleash his unbridled vision and talent. I wondered where the church’s commission ended and the painter’s expression and account began.

Staring at the ceiling treasures of Bohol, the largest works of art in the Philippines, brought forth a glimpse of heaven and a taste of the divine inspiration that touched Francia. And fluency took its leave.

In 2013, I had the pleasure of meeting Guy Custodio in Albuquerque, Bohol. The famous artist was working on restoring the ceiling frescoes of the church in Santa Monica at the time. Francia’s original paintings required rehabilitation because they had severely degraded. With the help of locals he had trained to assist him, he meticulously and patiently worked on each of the original sheets that comprised the ceiling.

Following a local artist’s botched restoration of the Anda church in 2022, Guy Custodio and the RCG team, under the direction of the National Museum of the Philippines, are currently working hard to consolidate the original paintings.