- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

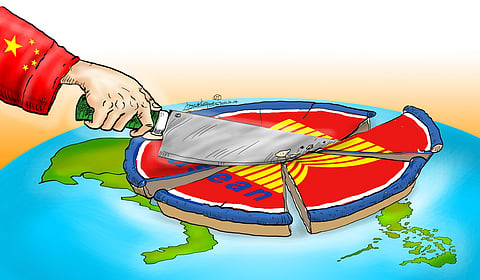

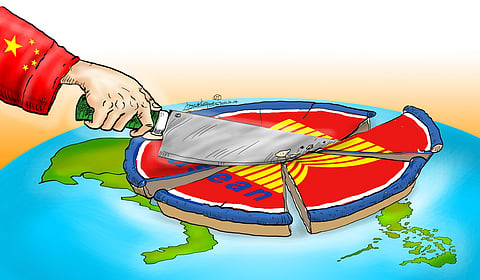

Defense Secretary Gibo Teodoro’s recent assertion that China is employing a “divide and rule” strategy to undermine the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a reflection of the mounting concerns about Beijing’s influence over the region.

Teodoro has called on the international community to prevent China from defining ASEAN centrality on its own terms, suggesting that the situation is far more complex than a simple power struggle.

Beijing’s strategic ambitions in Southeast Asia are no secret. The region, with its rapidly growing economies and strategic waterways, is a key component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a vast infrastructure and investment project designed to link Asia, Africa, and Europe. Additionally, the South China Sea, a contested body of water through which one-third of global shipping passes, is of immense importance to China’s maritime ambitions.

China has sought to assert dominance in the region, particularly through territorial claims in the South China Sea that overlap with those of several ASEAN member states. However, outright control of these waters is not necessarily the sole objective. Instead, China’s divide and rule strategy aims to sow discord among ASEAN nations to prevent them from forming a unified stance against Chinese encroachments.

China’s strategy revolves around leveraging its economic power and political influence to drive a wedge between ASEAN members. While Beijing might offer economic carrots such as infrastructure investments, trade deals, and loans to individual states, it simultaneously applies pressure on others — particularly those who challenge its territorial claims or resist aligning with its political interests.

For example, China’s significant investments in countries like Cambodia and Laos have led to these nations often siding with Beijing on regional matters. Both countries have blocked ASEAN from issuing joint statements critical of China’s activities in the South China Sea, thus weakening the bloc’s collective bargaining power. This manipulation of weaker states undermines ASEAN’s traditional consensus-based approach to decision-making.

Meanwhile, other countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines, which are directly involved in territorial disputes with China, have been more resistant to Beijing’s influence. Yet, their efforts to galvanize regional support against China are frequently undercut by Beijing’s backroom deals with their more China-aligned neighbors.

The concept of “ASEAN centrality” refers to the idea that ASEAN should be the primary driver of political, security, and economic cooperation in Southeast Asia. It positions ASEAN as a neutral platform for resolving regional disputes and engaging with external powers. This centrality is vital to ASEAN’s identity and its capacity to manage relations with external powers like China, the United States, and Japan.

Teodoro’s call for the international community to prevent China from defining ASEAN centrality underscores the threat that Beijing’s influence poses to the bloc’s autonomy. By picking off individual members and fostering dependency through economic or political favors, China seeks to redefine what ASEAN centrality means in practice, turning the bloc into a passive facilitator of China’s regional ambitions rather than an active promoter of its own collective interests.

If China succeeds in redefining ASEAN centrality, it could effectively neutralize the bloc as a counterbalance to its own power, reducing ASEAN to a set of disjointed states unable to collectively oppose Chinese expansionism. This would not only undermine Southeast Asian sovereignty but also embolden China to exert its influence more aggressively across the region.

The international community has a vested interest, too, in preventing China from dominating ASEAN. Countries such as the United States, Japan, Australia, and even India have expressed concerns over Beijing’s growing influence in the region. These nations have promoted alternative investment and security arrangements, such as the Indo-Pacific strategy, to counterbalance China’s growing sway. However, these efforts can only succeed if ASEAN remains united.

Teodoro’s plea for the international community to take a more active role therefore suggests that ASEAN alone may not be able to counter China’s divide and rule tactics. While external powers can help fortify the region’s infrastructure and security capabilities, they must also respect ASEAN centrality and work in concert with the bloc rather than unilaterally. This multilateral approach is essential to ensuring that ASEAN does not become a battleground for external powers, which could further destabilize the region.