- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

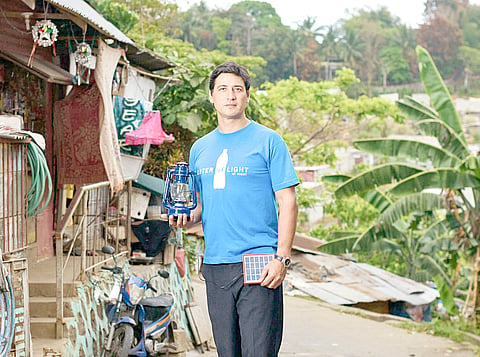

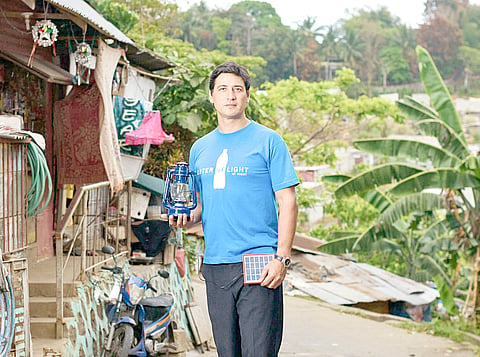

It has always been Illac Diaz’s vision to address energy poverty, a critical issue that affects nearly 800 million people worldwide. The entrepreneur is leading a groundbreaking initiative that would light the world, one liter at a time.

Liter of Light works with families, local cooperatives, volunteers and partners to build simple solar reading lights, mobile charging systems and street lights using readily available materials.

The design is simple: a transparent plastic bottle is filled with water plus a little bleach to inhibit algal growth and fitted into a hole in a roof. The device functions like a deck prism: during the daytime, the water inside the bottle refracts sunlight, delivering about as much light as a 40–60-watt incandescent bulb. A properly installed solar bottle can last up to five years.

Through its interactive programs, Liter of Light has illuminated one million lives a year, across more than 30 countries since 2013.

The campaign was honored with The World Habitat Award in 2014, Zayed Future Energy Prize in 2015, The St. Andrews Prize for the Environment in 2016, Asia-Pacific Social Innovation and Partnership Award for empowering diverse groups to build solar lamps during the pandemic in 2020.

On the other hand, the Theory of Light, a climate change film by Liter of Light and TBA Studios, premiered at the Expo 2020 Dubai.

Diaz, 2022 Conrad Manila’s champion of sustainability awardee, sat down on DAILY TRIBUNE’s Pairfect show with managing editor Dinah Ventura for an engaging discussion on the solar lighting movement.

DAILY TRIBUNE (DT): What challenges have you encountered since starting Liter of Light?

Illac Diaz (ID): I think it [energy poverty] is one of the greatest threats or crisis points for the Philippines. Yet because it moves so slowly, people are not addressing it.

For us at Liter of Light, we want to show that we not only need to address certain things but we also can bring this leadership abroad. It was important to me to show that we, from the Asia Pacific, are not only victims but can also be a voice in climate change. We offer solutions and act on them.

DT: Take us back to when you started Liter of Light.

ID: I’ve done several social enterprises. I think first of all we have to understand that a social enterprise has a 10 to 15-year time frame here.

For many parts, doing good was about charity. And when you do charity, you’re asking for a handout, ‘help me,’ ‘give me money so I can do good.’ It’s the most embarrassing and difficult thing, especially in the Philippines where people don’t tithe or donate regularly. But they’re the most generous. They give money to their family and scholarships in the tribe. That’s why they were not able to do extension ng bahay or convert the garage because it just did not work in a Filipino situation.

Social enterprise came along about 12 years ago and I realized that using business tools, but with a broad perspective of not just saying how much money I make. What about the employees or what about society? The most difficult one is about the environment. As long as I make money in the narrow sense of business. Social enterprise is not, we have to address employees and society at large because no one can just build an island of wealth.

The most difficult one was really this attachment with the environment, that it was something that could be at the expense of progress.

Nobody expected on the world view that it would be the extinction of a species. When they say let’s save the world, they don’t talk about Mother Nature, they’re saying us. If you say save the world, it’s like the world will go on way, way past us. It’s gone through so many, but it’s us who cannot survive living conditions of two degrees or three degrees. That’s what the mindset was.

I started building schools. When typhoons hit the place where people run to and their houses start shaking with above 150 kilometer per hour. The reason we have such a high number of people that die is that communities go to the schools to find shelter and these schools are built only for kilometer-per-hour winds. They’re all packed in the classrooms and then it collapses on them. I was interested in looking for new ways to build it so I did Earth and Schools, with stuff that you don’t need to bring cement, steel and glass manufactured.

There was a time before where people used to make their own houses and there are churches up to today in Ilocos Norte that are standing after 300 plus years. There are technologies that we forgot and so I wanted to go back and say if the people on the front lines, in the rural areas are the first ones to be hit by climate change they should be able to build at least with indigenous technology instead of waiting for cement, steel, glass which is the most expensive.

One of the things that I’ve also realized as I built schools is nobody was going to put up electric posts and light up my schools.

DT: Did you look for that actively or research it?

ID: I built these schools out of bamboo. I started building the first schools out of soil. Not the adobe blocks but with Earth bags.

Teachers were asking me how to light up the classroom. Solar is nothing that I invented, but we can buy the parts. We can buy MOSFET and LEDs. We can start building with these simple materials.

What I didn’t expect was, the teachers and the parents when they went home they started replicating some of the technologies and renting them. I found out later on that one of the most expensive things in the provinces was kerosene. Okay yes, you need to keep the house lit. You always have to almost spend 30 percent of your income to buy kerosene or wood or any kind of way to keep your house lit. They started renting it. I started asking them, why do you need two? Why do you need three? Why do you need five? ‘Yun pala it became a business for them.

During typhoon “Haiyan,” I was called and they asked me ‘you know we cannot import solar lights for these disasters. Is there a way for you to build it with local parts because it’ll take five months to get it from China or India to get 7,000 pieces.’ I said okay so people already knew that I build solar lights. I didn’t invent it. We already had the technologies but nobody was making the products. That’s when I experienced the first large-scale implementation of solar light building. I went to the women’s cooperatives and asked them to build it. I saw that there was a big chance to bring green technologies not only to solar plants but also start to build green jobs on a village level.

Liter of Light is LEDs, we make them out of bamboo, also out of pottery. The circuits of this are simple, these are MOSFETS and radio parts. There are four components with resistors diode. In India, we manufacture these things by hand. You can cut a big panel into strips and from five watts. You can make it into two watts or lower. We have mobile chargers, street lights, we have a way to teach people how to fix it.

That’s how we learned that we can have something, that everybody can be a change-maker from home.

DT: Was that the whole point of the challenge? What was your purpose?

ID: It was hard for me to explain that we should invest in what is called appropriate technologies. That we should be able to make it essential, especially in a country that was being hit by this kind of climate change.

Of course, the other side is also you know constant brownouts because we don’t have enough power plants to you know light up the country. People are scheduling it. That we should put the capacity for energy in their hands. t was hard to explain to people that solar lighting can be in your hands. And then they say, ‘ah kaya pala.’

DT: How has Liter of Light evolved through the years? What does it look like now in terms of design and components?

ID: The Liter of Light, the core concept, was to make myself obsolete.

Liter of Light was trying to say how can we start a transition in the Philippines, remember there are 13 million without light and many more cannot afford electricity. How do you transition that into our way of having cleaner access to energy? What we did was what is called the daylight, a plastic bottle with three ml of bleach to keep the water clear. The thing with the plastic bottle is that it’s built so strong that if you throw it around it’s indestructible.

Then you put it through the roof, one half to another half. Then we put the flushing on the top roof so the water will go up and then it will flush down right so it doesn’t go.

The point is that people don’t understand that there is darkness even during the day here in the Philippines. What happens is you have a house, then you put a wall and then somebody else puts a house. If you go to Tondo, there’s no light coming. Roofs are sticking next to each other, there are no windows. People have kandila. They have to have lanterns, they have to have some kind of lighting inside their house. How can you make them save energy during the day? They can replicate it by buying the same parts without me.

DT: You mentioned that you also make other things other than the light?

ID: Mobile chargers. Remember you know during the storm there were a lot of bunkhouses.

We learned how to light up the bunkhouses first with plastic bottles. There were two plants soft-drink plants that were destroyed in Tacloban. We don’t use very thin water bottles, we use thick ones. We started putting them in the bunkhouses and then later we started having corridors of light so women could go from the aid facility to their tent without being robbed or harassed.

DT: Tell us about your recent victory in Dubai.

ID: It’s very important in the whole scope of the discussions on climate change that in a way Filipinos are on the losing end of the narrative. First of all, a lot of the foreign films made or funded here are by Filipinos there should be a winner and there should be a loser in the narrative. Unfortunately, in the narrative, it’s always the Filipinos that are destroyed, devastated, destroyed environments. You know, that we have to help them.

That creates a lot of climate anxiety for young people who watch these movies like there’s no other way except to wait for help. Or there’s nothing that we can do, we’re on the way down. The whole point for me, is we can put a little bit of you know storytelling in our hands. There could be some kind of brown heroism, not only Al Gore, not only Greta Thunberg. We can also have a voice in this climate change.

Liter of Light has created space for new voices to be heard, reminding each person that they can make a difference.