- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

China’s usual mouthpiece has mockingly reported that the Philippines is only getting psychological comfort from the United States with its pledge of an iron-clad commitment to rush to the aid of the country in case of an armed confrontation based on the provisions of the Mutual Defense Treaty.

Beijing, it seems, is being emboldened by the timid response of the US to the series of aggressive actions China has taken to block supply missions to Filipino soldiers stationed on the grounded BRP Sierra Madre.

The aggression is calculated to gradually intensify in time to test the resolve of the country’s superpower ally.

Aside from the occasional joint patrols and naval exercises with our Western allies, the tepid response is what Beijing is ridiculing.

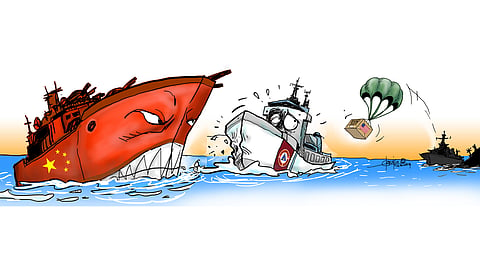

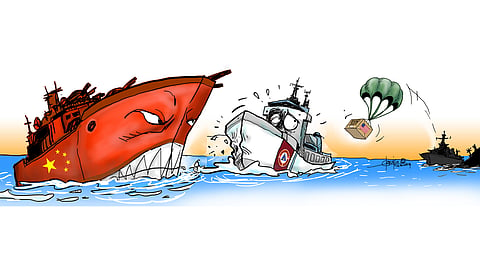

A case in point is the recent ramming by a China Coast Guard (CCG) vessel of a supply boat that severely injured a Philippine Navy crew.

As in past skirmishes, China insisted the Philippines had violated an agreement by sending a supply vessel and two inflatable boats to Ayungin Shoal.

In Beijing’s narrative, the supply ship “deliberately and dangerously collided with normally sailing Chinese vessels.”

Such propaganda is far removed from the truth as there is no person with a normal mind, much less that of an experienced crew, who would dare smash a small boat into a hulk of a vessel of the CCG.

As expected, China accused the Philippines anew of provocation to justify another of its bullying acts.

“The statement from the US State Department and its officials is nothing but a cliché. The US stance pretends that it is still the ‘world’s police’ and the master of the Asia-Pacific region,” the Beijing megaphone taunted.

The sad reality is that China may have reason to be smug about what is transpiring in the contested area.

While a challenge from a US military vessel is out of the question for now since it would risk a rapid escalation of the conflict, a plan to send US Coast Guard ships to escort the supply vessels remains unimplemented.

Allies within the region could also be tapped for a more permanent coalition against China’s expansive movement.

The US and India, for instance, can take several steps to stabilize the situation in the area of dispute.

India has the naval assets to assert both the freedom of navigation and the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

What China is banking on is a sudden shift in the political winds after the November US elections where America’s commitment to the region may weaken and thus remove perceptions of China being isolated in the global community.

New Delhi, moreover, has a similar position as the Philippines in that the maritime dispute should be resolved peacefully via a mechanism agreed to between the claimant states, which potentially allows ASEAN and the United States a role in pushing a solution.

The role of India remains understated but it can be the counterbalance to China’s increasing despotic behavior in the region.

India and Vietnam, for instance, have a joint oil exploration project that started in the South China Sea.

For a long time, China did not issue any comment on the project but in the early 2000s, it objected to India’s role in the venture.

India’s response was to assert the right of its state-owned enterprise to carry out the project as part of its legitimate economic interests while also helping Vietnam boost its coast guard capability through the sale of patrol boats. India’s warships also made frequent port calls to Vietnam.

India’s experience may be a model for the US where strong words are necessarily backed by concrete assistance.