- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

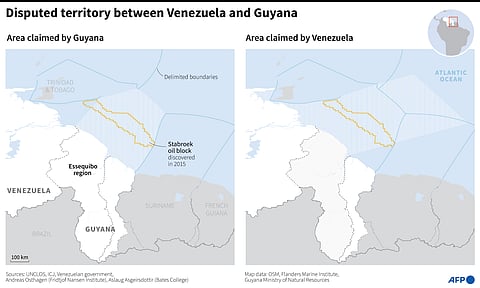

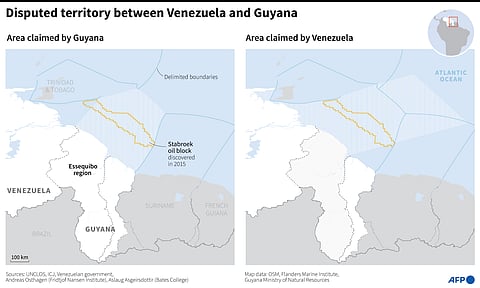

A decades-old dispute between South American neighbours Guyana and Venezuela over the oil-rich Essequibo region has highlighted the difficulty of tracing maritime borders.

AFP has talked to experts in a bid to shed light on how sea frontiers are decided under international law.

Complicating matters is the fact that sea borders in turn depend on land borders, also in dispute in the Essequibo case.

Article 15 of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea acts as a reference for defining maritime borders between two states with opposite or adjacent coasts.

However, Aslaug Asgeirsdottir, a professor at US Bates College and expert on ocean governance, says it does not specify where the line which forms the maritime border should start.

"In practice, the lines which have been determined by negotiations between states start from the place where the land border meets the sea, then continues along equidistant points from the two countries' coasts, up to a limit of 200 nautical miles," she says.

To determine which state has sovereignty and where, the law designates several zones: territorial waters (12 nautical miles from coast), the exclusive economic zone or EEZ (24 to 200 miles) and international waters (over 200 miles).

A country's underwater continental shelf, including the seabed and subsoil in which the oil is found, can extend beyond the EEZ.

"Sometimes circumstances justify the tracing of the border which strays away from the equidistant line," says Martin Pratt, director of Bordermap Consulting.

Beyond territorial waters, the UN convention just calls for "an equitable solution", he says.

States have several options for settling border disputes, Andreas Osthagen, a researcher at Norway's Fridtjof Nansen Institute and expert in maritime law, wrote in an article in Ocean & Coastal Management.

They can negotiate, go to the UN's International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, or another court like the Hamburg, Germany-based International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

Or they can seek arbitration, including at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague.

If the ICJ comes down on the side of Guyana in the Essequibo case, the maritime border could stretch in a line equidistant from the two countries' coasts, from the point the land border ends, said Pratt.

If Guyana loses, however, "the two states would have to negotiate a new land border, and the maritime delimitation would start at the place it reaches the sea."

Osthagen says there are maritime border disputes on every continent.

In 2020, only 280 out of the 460 potential borders had been agreed on. Nearly 40 percent (180 borderlines) remained under dispute, he said.

Among the maritime borders which had been agreed on between 1950 and 2020, 95 percent were through negotiations, he said.

Rising sea levels due to climate change can affect border delineations.