- NEWS

- the EDIT

- COMMENTARY

- BUSINESS

- LIFE

- SHOW

- ACTION

- GLOBAL GOALS

- SNAPS

- DYARYO TIRADA

- MORE

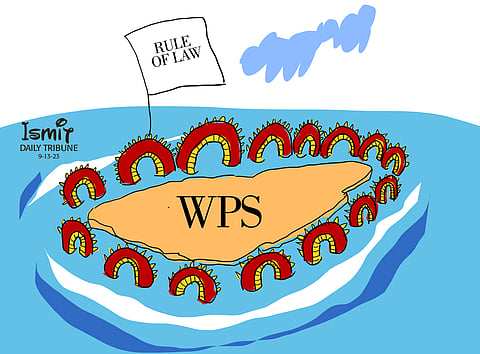

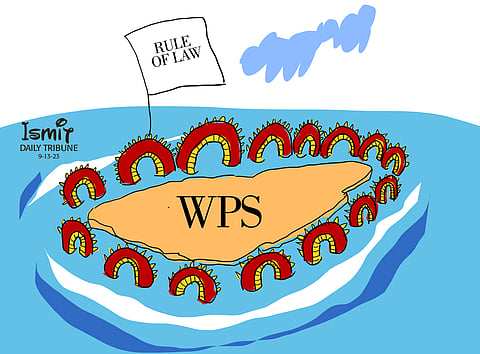

The United States, with all its influence and might, cannot take the moral high ground in the West Philippine Sea dispute since it is not even a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea or UNCLOS.

On the other hand, China, which is being accused of not following international norms and laws, is a signatory, which is why it insists that countries that want to have a say in the dispute should first recognize UNCLOS.

Ironically, the Permanent Court of Arbitration's invalidation of the nine-dash line claim of China, which the US said China should abide by, was based on UNCLOS.

Most of the world's nations are signatories to UNCLOS, known as the "Constitution for the oceans."

The treaty provides guidelines for how nations use the world's seas and natural resources.

It also contains mechanisms for addressing disputes, such as the current one between the Philippines and China.

Beijing's position is that while it acknowledges UNCLOS, it does not recognize the arbitral ruling since it did not participate in the proceedings.

China, thus, gets the brownie points when it accuses the US of hypocrisy for meddling in the WPS conflict.

According to China, the US is always selective when it comes to applying international law.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry official noted that it urges others to abide by international law while refusing to ratify the convention.

Instead of referring to UNCLOS, the US cites "accepted rules" of international law and "rules-based order," which, geopolitical experts said, are abstract terms compared to the more specific UNCLOS provisions.

Former US President Ronald Reagan rejected the UN treaty in 1982 due mainly to concerns about rights to deep seabed mining.

Conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation said those contentious provisions were revised in 1994, which led former US President Bill Clinton to support UNCLOS. The treaty was then submitted to the US Senate, where it was stalled.

Since then, every US president and most of the military's top officers had publicly supported the signing of the treaty, but it never gained the two-thirds majority support needed in the US Senate for ratification.

The UNCLOS ratification died quickly in 2012 when at least 34 US senators opposed it.

Republicans held that UNCLOS would undermine US sovereignty by transferring ownership of the high seas to the United Nations.

Geopolitical analysts said any US attempt to pressure China over its rejection of the arbitral ruling would be complicated because Washington had yet to ratify the treaty on which the Philippine complaint is based.

However, Heritage Foundation senior research fellow Steven Groves said, "China is going to disregard any negative outcome from the arbitration whether or not the US is a party to the treaty or not," which is the common thinking among those opposed to the treaty's ratification.

One of the critical concerns of those against acceptance of the UN convention is that the US will be deluged by "environmental lawsuits."

The bottom line is the US can speak out strongly in support of its allies in maritime disputes if it only recognizes UNCLOS.

The US "could say a lot more, and probably much more convincingly," if it were a party to the treaty, Andrew Chubb, a China expert at the University of Western Australia, said.

The US needs to improve the maritime rift as it operates outside the recognized international rules that bind even China.

If the US cannot convince its politicians to accede to international norms, how can it fare better with China?